Where Does the Past End and the Present Begin? The Temporalities of Propaganda in the Russian War on Ukraine

Daria Khlevniuk, Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Amsterdam

GN

Boris Noordenbos, Associate Professor of Literary & Cultural Analysis at the University of Amsterdam

International and domestic influence campaigns often root themselves in references to the past. Think of populists and their nostalgic appeals to the “golden old days” through slogans like “Make [Country] Great Again” – where “again” does much of the heavy lifting, while the “great” days of yesteryear remain unspecified. Such references are not just rhetorical flourishes; they are deemed effective, at the very least, by those employing them. Despite a growing body of research on memory’s role in propaganda and disinformation, much of the focus has been on what stories are told and which pasts are referenced. The question of how these stories are constructed – and how they structure time so as to make the past relevant for present-day agendas – has received far less attention. As part of a recent initiative branching from the EU-funded Conspiratorial Memory research project at the University of Amsterdam, we set out to explore precisely this question: How does propaganda invoke the past to reshape perceptions of the present? We presented the results in a paper titled “The temporality of memory politics: An analysis of Russian state media narratives on the war in Ukraine,” published Open Access in the British Journal of Sociology.

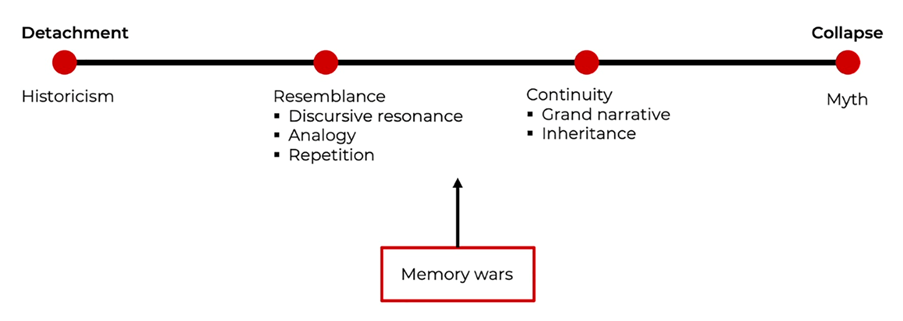

The Russian invasion of Ukraine offers a compelling case study for this inquiry. Ever since 2014, when the conflict began, references to World War II have saturated state-aligned Russian reporting, framing the war against Ukraine as an extension of the “Great Patriotic War.” As is widely observed, the Soviet victory over Nazism holds a unique position in the Kremlin’s communication, serving both as a cornerstone of national identity and a tool for political legitimacy. Focusing on the most prominent state-aligned news outlets, we examined a random sample of 516 Russian media messages from a broader dataset of over 5,000 texts published between August 2021 and August 2022. These messages combined reporting on the current war in Ukraine with references to events, episodes, and figures from World War II. What we found was a series of distinct temporal modes connecting past and present, i.e., a continuum of discursive and narrative strategies through which the (mythologized) past (the Great Patriotic War) was rendered relevant to the perception of the present (the Russian war on Ukraine).

Figure 1. Typology of memory politics’ temporal structures.

At one end of the continuum lies what we termed historicism. Rarely encountered in propaganda, historicism appears when media outlets present the past in a seemingly neutral tone, akin to a history lesson. The goal here is subtle: to guide audiences toward drawing their own connections from the historical past to present-day affairs. While seemingly innocuous, this strategy is far from agenda-free. By encouraging audiences to “connect the dots” and notice “the parallels” all by themselves, historicism creates an illusion of disinterested historiography, while steering the public’s current perceptions in a desired direction.

More commonly, we observed strategies of resemblance, in which history is invoked to foster associations with the present. This approach can manifest in straightforward name-calling (discursive resonance), where historical markers are employed nominally, with the suggested comparison remaining underdeveloped. A notable example is the frequent labeling of the Ukrainian army or political establishment as “Nazis,” a practice that taps into deeply ingrained, affect-laden Soviet discourses. Without elaborating on the history of World War II, such name-calling implicitly casts the enemy as the embodiment of ultimate evil while positioning Russia’s present-day actions as part of an existential struggle.

However, resemblance strategies can also involve more deliberate and extensive historicizing. As a subset of the resemblance type, we identified analogies, which suggest that the understanding of current events benefits from their comparison with the Great Patriotic War. In analogy-based reporting, we found parallels drawn between Zelensky’s advisor and Goebbels, but also, for instance, between the Soviet defense of the Brest fortress in June 1941 and the contemporary situation in the Donbas. One article of this type posed the rhetorical question of why the May 2022 events around the Azovstal’ factory in Mariupol were “so similar to Paulus’ surrender at Stalingrad.”

In yet other cases the suggestion is that the current events in Ukraine are not merely analogous to World War II but are direct repetitions of it. The difference between these two types – analogy and repetition – is reflected in the language (e.g., “just like” versus “again”) and lies in a distinct imagination of the temporal relations between past and present. In the logic of repetition, history is not a distant memory nor a source domain for comparisons with the present but an active, hostile mechanism that can be replicated. News articles of the “history-as-repetition” type tend to emphasize the “rebirth” of fascism or Nazism at Russia’s Western borders. Other war reporting in this category has it that Russian POWs in Ukraine are subjected to forms of torture that re-instantiate punishments employed by the Nazi occupiers in the 1940s.

As the continuum progresses, the distance between past and present diminishes further, and their interconnections grow tighter, resulting in what we term continuity. In this category, the past does not merely repeat itself but is portrayed in terms of an unbroken logical, causal, or patrimonial thread leading directly to the present. In continuity-type media messages, the public is, for instance, reminded that their real or symbolic predecessors, who heroically fought in WWII, would expect contemporary Russians to continue the battle against Nazism. A similar logic can be found in the portrayal of contemporary enemies. They are not just “similar” or “comparable” to the Nazis of the 1940s but are the biographical or ideological heirs of those same Nazis. By tapping into emotional and moral registers, this strategy fosters a sense of fear and duty that spans generations.

At the farthest end of the continuum lies myth, a term we do not use to imply that these narratives are “untrue” but to signal a mythical representation of time – one in which the conventional distinctions between past and present collapse into a singular reality. Unlike other strategies, myth dissolves temporal boundaries altogether, merging past and present into an ahistorical script. A striking example from the analyzed Russian media involves reports of Ukrainian fighters carrying around copies of Mein Kampf or original photo albums of high-ranking Nazis while fighting Russians. In such reports, historical distinctions are blurred, the enemy is portrayed as both the Nazi adversary of the 1940s and the contemporary Ukrainian opponent, effectively glossing over the obvious differences between them. Similarly, newspaper articles quoted Dmitrii Peskov, who, early in the war, commented on Russian casualties by saying that they marked “a great tragedy for all of us. At the same time, we admire the heroism of our military. Their feat will go down in history, a feat in the fight against Nazis, one might say, and in fulfilling this important, responsible task.” The “Nazis” (rather than, for instance, “neo‐Nazis”) referenced by Peskov are unmoored from their specific historical embeddedness. Referring to the historiography of the future (“their feat will go down in history…”), Peskov’s statement works precisely to erase historicity and to collapse the present war on Ukraine with the historical battle against Nazism, turning these two distinct moments in time into one timeless Russian task. Myth, indeed, fosters a sense of timelessness, where history is not simply recalled but actively experienced in the present. In this arrangement of temporality, the past is no longer a point of reference detached from the here and now; it becomes the very stage upon which the present unfolds.

Our typology draws attention to the temporal structures of politicized memory discourse rather than its themes. While we focus on the Russian state-aligned media sphere, we assume that the same temporalities may be used outside authoritarian contexts. We notice that the same historical event is often used to tell different stories about the present, depending on how the relations between past and present are organized. What drives the choice of one strategy over another? Context likely plays a role. For instance, during periods of military setbacks, propaganda narratives may lean toward the more emotionally charged strategies. “Continuity” or “myth” – which seeks to imaginatively insert contemporary Russians into cross-historical constellations – may serve to rally support at moments when pro-Kremlin public consensus is under pressure. In more stable times, simpler strategies of “resemblance” may suffice. Another critical question concerns audience reception: does invoking “continuity,” which frames individuals as the heirs of heroic fighters or evil villains, indeed generate greater engagement than discursive strategies that rely on more clear-cut lines between past and present? Understanding how audiences respond will be crucial to evaluating the effectiveness of these strategies and deepening our grasp of memory’s role in propaganda. These issues remain open for further research.