The Odesa Fire 2014. Part 2: Good-faith production of distorted knowledge

Aleksei Titkov, Sociologist, Visiting Fellow at The University of Manchester

This is the second part of a two-part blog post discussing how grassroots practices of broader Russian audience have shaped the popular atrocity narrative of the 'Odesa Khatyn'. The first part is available here.

III

Part 1 questioned approaches to studying propaganda and disinformation. However, I share with those advocating such approaches the key intuition about the influence of the media environment on the views of the audience. For the case under discussion, two types of media are primarily important: national TV channels and social networking platforms.

There are well-established concepts providing clear predictions that can be tested empirically. These are Andrew Hoskins' (2004) ‘collapse of memory’ model'for the case of TV-dominated media environment, and the ‘echo chamber’ model by Kathleen Jamieson and Joseph Cappella (2007). The ‘memory collapse’ model distinguishes between a period of intense TV coverage of a given event and a subsequent period when TV channels and their audiences move on to other topics. During a short period of intense TV coverage, the audience receives emotionally charged flash frames, which can later return in flashbulb mode, caused by visual images or keywords associated with the event. In turn, the ‘echo chamber’ model suggests that in a social media environment polarized by political conflict, each rival party seeks to create a relatively closed spaces in which the information received would confirm their political biases.

For our purposes, these explanatory models differ primarily in their assumptions about the nature of the relationship between professional journalists and the audience. In 'memory collapse' model, large institutional media, acting in concert, influence the audience as an irresistible force. As a result, patterns broadcast by institutional media are imprinted on audiences in the same way as early 'hypodermic needle' model suggested. The 'echo chamber’ model, on the other hand, refers to a competitive media environment in which audiences must take the initiative. The differences between professional journalists and ordinary microbloggers there seem secondary and more quantitative than essential.

In the case of the Odesa fire, a quantitative analysis of Ukrainian audiences (based on a May 2014 survey) by Henry Hale, Oxana Shevel, and Olga Onuch led them to conclude that the choice between competing interpretations of the incident was determined more by political identity than by TV channels. This means that the views of the Ukrainian audience in May 2014 were formed more according to the “echo chamber” model than the “memory collapse” model. The Russian media environment of this period can be defined as a combination of the state media dominance in TV broadcasting (close to the 'memory collapse' model) and a polarized social media environment (as in the 'echo chamber' model).

Because of the specific circumstances of the Odesa Fire both visual representation and versions of what happened were largely determined by social media. The street clashes in Odesa arose from a local episode, a march of football fans, which the national media of neither Ukraine nor Russia intended to cover in detail. Information about the dozens of people killed in the Trade Unions House became widely known only late in the evening, after the main daily news programs on national television channels had been broadcast.

As a result, on the morning of 3 May 2014, when Russian TV began covering the incident in detail, professional journalists had to rely on documentary evidence that had been published on social media and already selected as important in discussions there. TV journalists took from social media both primary documents and their interpretations. Even the general frame “Odesa Khatyn” was popularized by Russian TV with reference to the grassroots remarks. In the earliest detailed story on Channel One (Russia) at 12:00 on 3 May it was stated that: ‘What happened next, journalists and bloggers have already called the Odesa Khatyn’. Of course, Channel One put forward an interpretation that corresponded to its ideological position, but the fact it captured is true: the keywords really did appear late at night on 2 May and by the morning had spread across social media.

Figure 5. News release of Channel One (Russia) 3 May 2014 at 12 noon with the Youtube channels listed from which the videos were borrowed Source: Channel One (1tv.ru)

Thus, at the early stage, the relationship between Russian TV channels and social media can be defined as a symbiosis, in which ideas are produced primarily by social media, and TV channels broadcast them to a nationwide audience. Professional journalists, of course, modified the story to suit their vision, but these were merely individual variations within the general logic developed in social media.

The clear impact of Russian television channels on public opinion was that, from the variety of versions circulating in social media, state television selected only topics that would confirm the idea of a deliberate massacre.

The stunning effect of the Odesa Fire on Russian audiences in 2014 is confirmed by survey data. According to the independent Russia’s polling agency Levada Center, the, the Odesa Fire was considered the ‘most memorable event’ of recent weeks by 36% of respondents at the end of May 2014, 31% in June, 24% in July. In a survey on the most important world events of 2014, the Odesa Fire was mentioned by 14%, roughly on par with the Euromaidan and the military conflict in Eastern Ukraine. In their survey in May 2014, 80% of respondents consider pro-Ukrainian activists to blame for the deaths in Odesa. Without intense TV coverage, such widespread emotional involvement in the story and such consensus of interpretation would hardly have been possible.

IV

In the previous analysis, which focused on early representations of the Odessa fire, both the memory collapse model and the echo chamber model might have seemed relevant to the case. However, a later stage of representation, still much less studied, challenges both these models.

The memory collapse model correctly predicts that with the end of intensive TV coverage, social media also switches to other topics. Later, exactly according to this model, the theme of the Odesa fire came to the fore only in annual commemorations and in crisis situations such as the start of a full-scale war in 2022. What is unexpected for the memory collapse model is that some of the striking topics about the Odesa Fire that dominated the period of intense TV coverage later fall out of circulation.

At least one of them, the topic of the massacre inside the Trade Unions House, seemed ideally suited to become a flashframe defining the collective memory of the incident. One of the key images of this topic was a photograph of a dead woman in an office, who, according to an early atrocity narrative, was presumably pregnant and was brutally murdered. Both the image and the atrocity story behind it were shocking enough to be imprinted in the memory through the emotional selection mechanism. The great impact of this story on the audience is evidenced by the fact that it was the dead woman in the office that became one of the main themes of amateur poems about the ‘Odesa Khatyn’. However, over time, it became marginal, just like the once popular versions about poison gas or disguised provocateurs.

Figure 6. Guests of the talk show ‘Priamoy Efir’ (‘Live’) on the Russia-1 TV channel, 5 May 2014, discuss a photograph of a dead woman, an early iconic representation of the ‘massacre in the building’ version. Under the photograph is the talk show topic: ‘May Odessa: Khatyn of the 21st century.’ Source: Smotrim.ru

A distinctive feature of all the early topics that have gone out of circulation is that they are all factually incorrect. The same shift is visible among Ukrainian audiences. There, earlier unreliable versions, such as accidental self-immolation and the intervention of Russian saboteurs, have noticeably lost popularity.

The idea that audiences eventually reject disproved false stories is quite plausible from a commonsense perspective. However, neither the memory collapse model nor the echo chamber model predicts an increase in valid knowledge. The former assumes audience passivity, the latter focuses on distortion and bias.

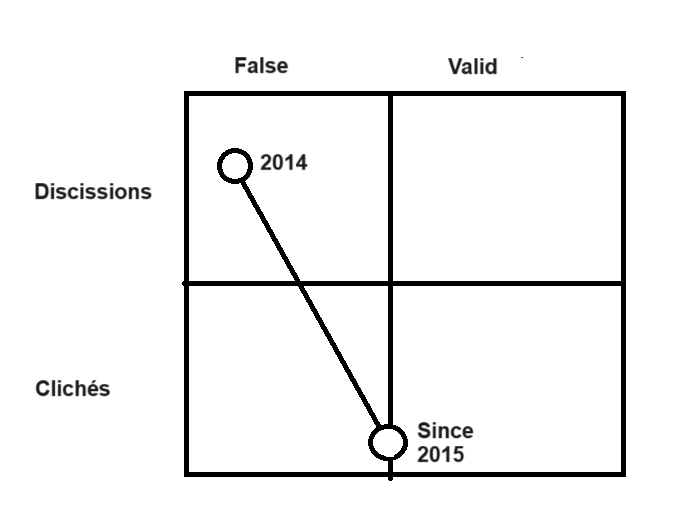

A comparison of early and late comments about the Odesa Fire on social media reveals two types of changes regarding their content and their form. The content became more substantiated after a set of factually incorrect topics left circulation. At the same time, the extensive discussions typical of the early stage ceased. These early discussions had much in common with rational scientific debate, evaluating, for example, the poison gas version using data from chemical reference books. In the later period, template phrases, intended to express unanimity among “our people” or exchange accusations with opponents, became clearly predominant.

Figure 7. Comments about the Odesa Fire in social media in dynamics

The changes can be understood as the consequences of a collective process that had some features of rational discussion and, after a few weeks or months, led to a stable state in which the collective knowledge is already considered unconditionally true and no longer requires discussion.

The results of this process appear contradictory. All the topics remaining through a collective selection can be called document-based, since each of them is associated with a real video fragment. At the same time, the later atrocity narrative still includes some gross factual errors that are easy to check and disprove.

A clear example of a distortion that could be easily refuted is the popular topic about pro-Ukrainian activists who allegedly shot at people trying to escape a fire. The visual basis for this idea is a video fragment in which a thick-set man known as ‘sotnyk Mykola’, in a bulletproof vest, shoots towards the Trade Unions House.

Nikolai Volkov (this figure’s real name) led a small pro-Ukrainian paramilitary group of up to a dozen people during the street clashes on 2 May. The nickname ‘sotnyk Mykola’ stuck to him after a viral short video by Odesa journalist Valeria Ivashkina. In this video, Volkov talks on a mobile phone, as the journalist suggested, with a ‘minister in Kyiv’, and then introduces himself to the camera as ‘sotnyk Mykola,’ with the Ukrainian version of his name and the mid-level rank (literally ‘commander of a hundred’), historically used by the Cossacks. Later, the daytime conversation between Volkov and the alleged ‘minister’ gave rise to conspiracy theories, and the footage of him aiming at the Trade Unions House became the iconic image of the Odesa tragedy.

Meanwhile, the full 24-minute video, from which the shooting fragment was cut, gives a clear indication that Volkov (sotnyk Mykola) acted ten minutes before the fire: the shooting occurs at the 7th minute, the fire starts at the 17th minute. The full video, published on the night of 2-3 May, was always available in the public domain and has received, to date, more than 600 thousand views, but this did not prevent a simple mistake from taking root. Why this happened is an important question that will have to be left out of the equation this time.

Figure. 8 Sotnyk Mykola shoots at the Trade Unions House. A fragment of a video published on the night of 2-3 May 2014 by widely followed blogger Anatoly Shariy. The image is from a republication of the fragment on the social networking site OK.ru (2016) with the explanatory heading ‘Odesa. Shooting those getting out of the fire.’

Thus, we are facing a controversial process that combines rational selection in a broad debate with great distortions due to partisan bias. Rational criticism based on video documents influenced the fact that several erroneous versions went out of wide circulation but did not prevent other gross errors from taking hold. To understand these dynamics, both media and memory scholars must move beyond the usual focus on distortion as a primary concern. Objective knowledge and distortions must be recombined into a common explanatory framework.

A guideline for a new perspective is provided by the sociology of knowledge. The symmetry principle, proposed by David Bloor in the 1970s, suggests that both objective knowledge and biases are equally research problems; both result from practices conditioned by social context and can be explained by the same set of causes.

Academic laboratories and politicized echo chambers are, of course, different in many ways. But a universal approach that sees them as invariants of good-faith knowledge production can improve our understanding of both.